Location, location, location: Keeping track of risk with Microsoft Authenticator

Published by Jed Laundry on

One of the common security controls our customers implement to keep themselves safe and secure is region-specific conditional access policies. It’s a bit of a mouthful, but essentially, these policies mean that when your employees are inside their approved region (for example, in the United States) they can log in and access everything, but in other regions (for example, while on holiday in Europe or Asia), they can’t, or need to take additional steps to verify their identity.

The way this works is by looking at the source IP address, and finding the corresponding address in a database of locations.

This tried-and-true method to roughly geolocate the source works most of the time… except when it doesn’t:

- Where someone is using a virtual private network (VPN) to appear in a different country—for example, to bypass country restrictions on online video streaming services—any requests will also appear to be coming from this country.

- Where IP addresses are not correctly mapped against their country or region, as happens when ISPs purchase IP address space from other companies, or use new services like Starlink.

- Where an attacker with a compromised user’s password uses a VPN or virtual private server (VPS) to geolocate themselves in a different country, such as the victim’s country.

Where the user is roaming on another mobile network in another country, traffic will appear to be coming from their home country, allowing them to access your network while out-of-region.

Resolving risk

While the first and second cases are a mild annoyance with little security risk, the third and fourth cases are more interesting. If your risk management policies or customer requirements prohibit you from accessing sensitive information from, let’s say, China, it’s not ok that when you access resources from China, it looks like you’re still in the United States.

To help resolve this, Microsoft have added a feature to the Microsoft Authenticator app: instead of relying on the source IP address, you can now require that the location is taken from the GPS of the user’s mobile phone.

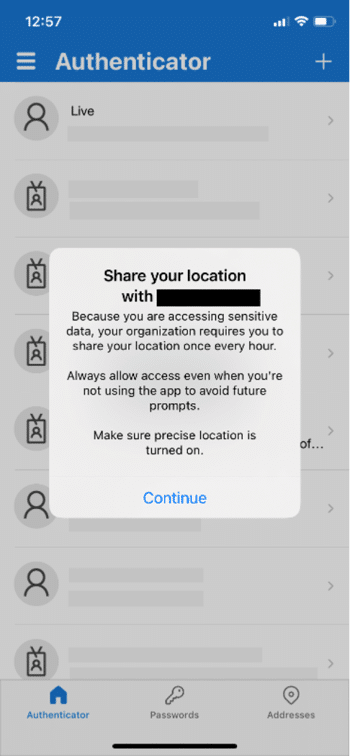

When you enable this feature, the next time your users sign-in, they are prompted by the Microsoft Authenticator app to share their precise location, every hour.

This presents a couple of problems:

- Tracking the exact location of your staff and contractors in a way that’s highly visible to them may leave them uncertain about how or why this data will be used, which in turn may cause nervousness and distrust.

- Enabling this feature disables the ability to use passwordless sign-in. Given the number of password-based attacks, passwordless credentials are more secure, and therefore, increasingly popular. Forcing people to use a password is a step backward in the broader scheme of best practice security hygiene.

Many companies don’t provide work phones, instead relying on staff and contractors to use their personal phones for authenticator apps. This is broadly acceptable, because these apps don’t create privacy issues; they don’t monitor the phone or have access to any information, especially personal content including photos and location data.

This could change, however, if employees are expected to allow workplace-mandated apps to constantly monitor their location.

Finding the right balance

There are very few employees who would believe that a company’s security should come at that sort of cost.

Security initiatives need to consider the privacy and end-user impact. While there are cases where GPS-based location tracking of people might be appropriate, we believe that all organizations are better off removing the risk of password compromise by removing passwords entirely, and moving to passwordless authentication.

It’s also important to note that this is not an attack on Microsoft. We know that Microsoft values and understands privacy, and in fact Microsoft does say this feature should only be deployed in exceptional circumstances.

If you do need to use this feature, you should consider a Privacy Impact Assessment, what needs to be discussed with your people, and what mitigating factors can be put in place before implementing it.

Hopefully this serves as a reminder that to paraphrase Dr Ian Malcolm, you’re not so preoccupied with whether you could do something, that you don’t stop to think if you should.